Table of Contents

Introduction to Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a cutting-edge member of the microscopic techniques known collectively as scanning probe microscopy (SPM). The underlying principles of SPM are markedly distinct from those of light and electron microscopy. SPM methods are used to study the surface properties of materials by scanning an extremely fine probe over the specimen surface. This relatively recent technique emerged in 1981 when Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer developed the first working SPM, specifically the scanning tunneling microscope (STM).

Fundamentals of Scanning Probe Microscopy (SPM)

- Early Development: The scanning tunneling microscope, the first SPM, uses a fine metal tip held at a high voltage to scan the surface of a specimen in a raster pattern. The primary measured quantity is the tunneling current between the tip and the sample. The STM operates in two modes: constant current mode, where the current is kept constant through a feedback loop causing the sample stage to move, and constant height mode, where the tip scans at a constant height and current is recorded at each point.

- Limitations of STM: STM cannot study non-conducting surfaces, which led to the development of alternative microscopes, including the atomic force microscope (AFM).

Atomic Force Microscope (AFM)

- Basic Components: AFM operates by measuring the force between a sharp probe and the specimen surface. It consists of three primary components: a probe, a positioner, and a processing unit. The analogy to feeling objects in a dark room can help understand its working principle; just as fingers distinguish between objects by touch, the AFM probe scans the specimen surface to gather data.

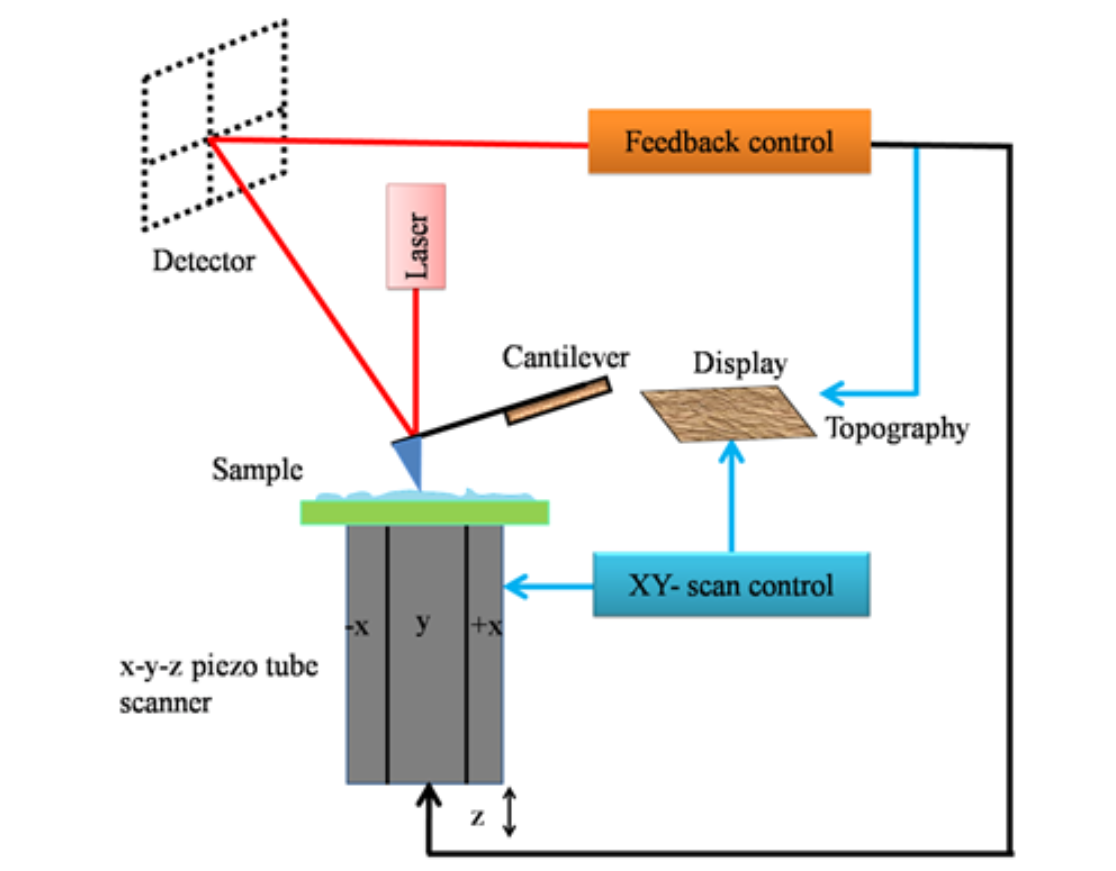

- Cantilever and Piezoelectric Elements: The AFM has a pointed probe attached to a cantilever. Positioning of the cantilever relative to the specimen is achieved using piezoelectric elements known as scanners. In earlier AFMs, these elements were part of a piezoelectric tube that positioned the cantilever in three dimensions, often causing crosstalk between X, Y, and Z scanners. Modern AFMs use separate scanners for the Z-direction to reduce errors.

- Laser Detection System: A laser beam is focused on the reflective surface of the cantilever. The laser’s reflection onto a position-sensitive photodiode quadrant detects cantilever deflections caused by interactions with the sample. The displacement of the laser spot is analyzed to calculate cantilever deflections.

Modes of AFM Operation

- Constant-Force Mode: The distance between the tip and the specimen can change during scanning.

- Constant-Height Mode: The force between the tip and the specimen is allowed to vary.

Imaging Modes

- Contact Mode AFM: The tip remains in close contact with the specimen, scanning in the repulsive regime. High frictional forces make this mode less suitable for soft samples like biological specimens.

- Non-Contact Mode AFM: A cantilever with a high spring constant oscillates near the sample in the attractive regime. This mode measures changes in oscillation amplitude and phase, suitable for soft samples but with lower resolution.

- Intermittent or Tapping Mode AFM: A stiff cantilever oscillates so that it intermittently touches the sample, allowing high-resolution imaging and being ideal for scanning soft biological specimens.

Force Mode AFM/Force Spectroscopy

- Non-Imaging Mode: Force spectroscopy involves bringing the sample close to the cantilever, pushing it to cause deflections, and then withdrawing. The force-distance plot, known as a force spectrum, helps study tip-sample interactions and determine mechanical properties of specimens.

Resolution of AFM

- Comparable to Electron Microscopes: AFM can achieve resolutions similar to electron microscopes since it doesn’t rely on light or particles. The resolution depends on the tip’s shape and diameter, with Z-resolution often reaching ~0.2 nm or better.

Advantages of AFM

- Simple Sample Preparation: AFM requires minimal sample preparation. The sample can be directly placed on a smooth surface for scanning.

- Imaging in Solution: Unlike electron microscopy, AFM can routinely record images in solution, providing sub-nanometer resolution.

- High Spatial Manipulation: The AFM tip can mechanically manipulate specimens with high spatial resolution.

Conclusion

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) represents a significant advancement in microscopic techniques, enabling detailed surface analysis and manipulation at the nanoscale. With its versatile operation modes and superior resolution capabilities, AFM stands out as an indispensable tool in scientific research, offering unique advantages over traditional electron microscopy, especially in the study of soft and biological samples.